Dear Reader,

FOLLOWING the theme of constant misrepresentation of art and history by a fanatic pro-modern art media I thought it maybe helpful to share some light on one of the most misrepresented artists of today. I refer To Vincent Van Gogh.

While the National Gallery in London holds the painting enclosed below, it also holds other works by the same artist, which I do not think have been presented in a fair light and have been used to justify modernism in art at his expense. Likewise, the history of his life, whereby the alleged cutting-off of his ear to give to a prostitute was recently discovered by a lady in France to be a modern fabrication.

It transpires that he knew a young lady in Paris, who moved to the country. Shortly after he followed her, obviously holding feelings for her. She worked as a cleaner in a brothel, yes, but she was not a prostitute herself. However, she was apparently affected by their cynical view of life and of men, so therefore disbelieved Vincent’s genuine feelings and affection as a result. Unfortunately, by now suffering from ill health, we presume he said must have said somewhat in jest, ‘What can I do to prove my feelings?’. He then foolishly cut off his ear to prove it in reality. People have done mad things in love before and since. He was, however, suffering from ill mental health at that time, caused by over work.

The other facts that have come to light recently, have concerned the sales ability of his brother Theo’s wife, Vincent’s sister-in-law, who inherited all of his works upon Theo’s death. Successfully selling works in America, she claimed she would not sell the Sunflower paintings, as they were emotionally important to her. When presented with this view, the National Gallery in London was apparently convinced that she thought they were his best works and substantially increased its offer for these paintings until she agreed to sell. Thus in one stroke, these apparently became his best works, because of that high price.

By contrast the other wonderful conventional landscape painting in the museums in Paris which I saw (there are hundreds of them), have been ignored for a long time; many are technically brilliant, but traditionally executed properly and do not present that narrow slap-dash modern art view.

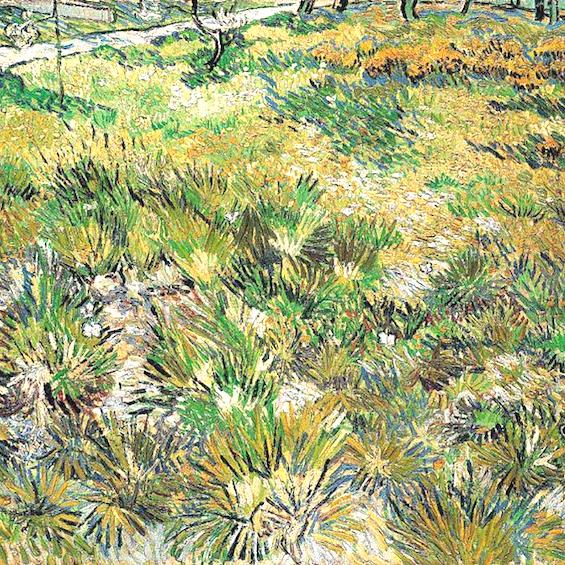

‘Long Grass with Butterflies’ by Vincent Van Gogh

As you look at this painting you become aware of how strong the foreground actually appears. Technically, by any standards, it is a terrifically strong three-dimensional painting.

Looking at those clumps of grass, they seem to burst outwards into life and allow you to feel the ground underneath. Equally you can almost feel the sharpness at the tips of those blades of grass under your fingers as they grow outwards to catch the light in many different directions.

If you half-close your eyes down (slightly squinting) and look at each piece of the ground in the painting where it is being modeled, then each separate piece easily leads on to the next, as well as moving upwards and downwards indicating where form itself moves back into space. We see an area of bumpy, broken ground that dips downwards and upwards again into the distance, moving from the middle of the picture outwards towards the edges.

At the same time, with your eyes still half closed, there suddenly comes a surprise and butterflies appear almost mysteriously.

How vibrant and alive this painting of long grass appears. It is achieved through the use of temperature and tone. The darker tone you can see, in the dark blades of grass and in the drawing of the space that contrasts strongly against lighter blades of grass.

Visually, another contrast appears in the earth underneath and there are tonal changes here as well. Van Gogh deliberately uses the yielding texture of the flora and the solidity of the soil to enhance his three-dimensional drawing and his temperature values within this scene. As a consequence, this is a charming painting of the rural countryside. It appears as a bright summer picture with terrific hot and cold temperature changes between yellow and green, orange and blue,

Van Gogh describes the physical experience in everything he draws and paints.

He frequently presents the wild, often awkwardness, which can be found in Nature and attempts to describe this with matching brushstrokes and style.

His draughtsmanship is uncompromising. Everything is drawn and painted using the same high degree of standard. This is equally true, whether it is in the foreground, in the mid-ground or in the distance. Everything in the work of Van Gogh is recorded with this same accuracy. This attention to detail and intensity in his work is frequently misunderstood.

In keeping with the Great Tradition, he advances the whole work at the same time. We could compare him with the works of Mahler in music or Keats in poetry, for there is a sense of an all-pervading completeness with respect to his personal craftsmanship, intellect and technical skills.

Many modern artists and critics seek to prove and justify the benefits of today’s abstraction in modern art by presenting the artist Van Gogh as their shining example.

In stark contrast, throughout his life, Van Gogh made numerous beautiful examples of realistic, traditional drawings and paintings in a conventional manner. There have been many exhibitions of Van Gogh’s work that have clearly showed this fact with a wide variety of his traditional work. Often they have contained numerous examples of traditional landscape painting and hundreds of landscape drawings, as well as natural drawings of peasants, buildings, trees and whatever life presented.

One of these exhibitions for instance, contained a picture of a bare tree in an apple orchard, obviously depicted early in the morning with dewdrops on its tiny branches and, surprisingly, it was completed in pencil. The work in that exhibition clearly demonstrated how traditional skills in painting and drawing can be applied and what a master craftsman Van Gogh must be considered.

Probably, due to the media who constantly show the same pictures today, people unfortunately tend to exclusively focus on those Van Gogh paintings when he was in a mental asylum or ‘The Chair’ and those kind of obscure works, thus ignoring the body of his work with numerous fresh landscapes.

In retrospect, obviously, it is foolish to only concentrate on a narrow view of Van Gogh’s painting especially when some of these were made during an unfortunate period in his life. It is also foolish to imagine these disturbed paintings are wholly representative of Van Gogh’s life and career.

It can never be correct to present a limited view of an artist’s work under such unfortunate circumstances. Let us take the work of art critics for example. Could we expect to see perfect examples of written work by critics after they themselves were afflicted with the malaise of a debilitating illness? How many would be able to achieve anything coherent? Compare this to Van Gogh’s efforts to paint during his illness and one can almost hear the numerous calls requesting compassion or understanding from critics if they found themselves in similar unfavorable circumstances.

Nobody is perfect in life. Realistically, Van Gogh could not have made perfectly drawn and painted works all of the time throughout his life any more than anybody else could.

Michelangelo bought back his own early works and then destroyed them.

Cézanne, who was the last painter we looked at, is often accused of ‘abstracting’.

Sadly, few critics allow artists to be human and have their ‘good and bad days’, within the complexity of human life. Practically, Cézanne’s supposed ‘abstractions’ were more likely to have been influenced by some difficulty he was experiencing with the work itself or with regard to his experience of constantly changing and developing his practical skills.

Indeed, talking about the life of an artist instead of his work is really childish. It is the work of the artist we are interested in. We are not talking about the life of a saint, nor should the public expect one. Artists would have to live different lives and have different priorities if this were the case.

Today, Van Gogh must be looked at afresh with regard to all of his work throughout his entire career. For it is ignorant to concentrate on work made during that period of mental illness and misfortune. Equally, it is all too easy to mock the afflicted, but a desire to be afforded a reasonable sense of human dignity, decency and compassion must hold true for artists as for everybody else with their personal lives and careers.

Ideally the art of Painting should be a lifetime of study for the artist and offer a lifetime of pleasure for the viewer.

© Charles Harris 2018 from ‘Trust Your Eye’.